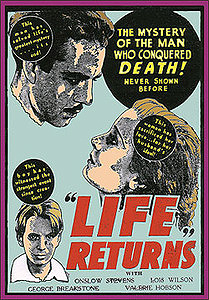

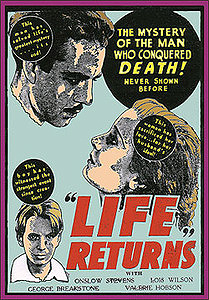

John Kendrick (Onslow Stevens), Louise Stone (Lois Wilson) and Robert Cornish (playing himself) are three happy college students out to change the world with their theory of bringing the dead back to life. At graduation, Kendrick excitedly tells his colleagues how he’s gotten them all jobs at a pharmaceutical company. The others object because a commercial firm can never share their lofty goals, but Kendrick is certain that their resources will complete the project faster, and abandons them. Kendrick becomes even more obsessed, and he also marries a socialite (Valerie Hobson) and has a child, though those aren’t important matters as we learn about the first only through a newspaper headline. As it turns out, Stone and Cornish were correct—as if that wasn’t really clear from the start—and the company wants him to break off his vital research to work on “hair growth brushes.” This disappointment is too much for him and he has a mental breakdown. He runs around announcing that he wants to bring the dead to life, which for some reason doesn’t go over well. Then his wife dies of…I don’t know…perhaps being poor… It isn’t explained. Perhaps she died of Valerie Hobson walking off this project in disgust; that makes sense anyway. His child is taken away by the state since Kendrick shows no signs of being able to take care of anything (how does he still have a house?), but the kid runs away and meets up with a bunch of escapees from an Our Gang comedy that all live in a club house. The kid’s much beloved dog is captured by the dog catcher and put to death. So now it’s up to Dr. Kendrick, with help from Dr. Robert Cornish—who is the greatest human being to ever walk the Earth; all praise to Robert Cornish—to bring the dog back to life in order to regain his son’s love.

As Life Returns was distributed by Universal, starred Onslow Stevens who was in House of Dracula, co-starred Valerie Hobson who was in both The Werewolf of London and Bride of Frankenstein, and is about a “mad scientist” bringing the dead to life, it has gotten grouped in with Universal Horror. It doesn’t belong. It also was banned in Britain, so it’s gained a mystique. It doesn’t deserve that either—the mystique that is; the banning is another matter.

This isn’t Universal horror. This is trash cinema of the lowest sort, trying and failing to exploit a recent headline. Produced by Scienart Pictures (its only film), not Universal, the news it was exploiting involved Robert Cornish, although perhaps “exploit” is the wrong word as it is more of a propaganda piece, or advertisement for Cornish.

In the early ‘30s Dr. Robert Cornish had theories on “bringing the dead back to life” which today we’d call reviving or using CPR. He wanted to work on humans, but this was frowned upon, so he got five dogs, suffocated them, and then immediately tried to revive them with adrenaline and rocking them on a “teeterboard.” It didn’t work well, but had some effect. Three died; the other two were brain damaged and blind, after which Cornish hid them away and claimed it was a success. He was fired from the UCLA because they weren’t idiots. So he decided to work from home on pigs, because nothing says sane and reasonable like killing pigs in your extra bedroom in order to bring them back to life. Of course killing animals in your home can get pricey and he wanted funding, so he tried to get some positive publicity with Life Returns. I don’t know if he approached the producers or they approached him. The idea was to build an emotional, fictional story around a recording of one of his dog experiments. So footage of the actual experiment is in the film (and as Britain isn’t keen on animal abuse in cinema, it was banned) and the movie starts with two different statements on how Cornish’s work is miraculous and important. No mention was made of him being a weirdo working at home.

Life Returns didn’t gain Cornish the popular acclaimed he desired, possibly because it’s a tedious film. He did pop back up in the news some years later when he wanted to bring a convicted child-murderer back to life after his execution. Needless to say, the authorities weren’t keen on this idea. That he couldn’t have done it didn’t stop him getting as much press as possible out of it.

It’s hard to express how horrible this movie is. At first I couldn’t imagine how they got Valerie Hobson to appear in this kind of trash, but I hadn’t realized she was only 17 at the time (or perhaps 16 during filming) and is only in it for a few minutes. Onslow Stevens didn’t have a shining career, but he rated better than this, so I assuming they just lied to him. Cornish gets top billing.

I can’t find a budget for Life Returns, but by the look of it, I figure it was in the hundreds. The setups are primitive with the camera generally sitting in one place and the result is ugly (though to be fair, no one has put any care into preserving this abomination). Stock footage is used which doesn’t match the shot footage (and I’m not only referring to the experiment, which does indeed match extremely poorly; in an early montage we see a college graduation which clearly is from a different source from the set-bound scene that follows). The movie starts (after a fade-out of Cornish’s face), for no reason I can determine, with stock footage of wheat and ploughing. I’m guessing they could get it for free.

There’s something gruesome about the dog resurrection scene, knowing that we’re not watching some kid’s pup that had been dead for hours brought back, but a dog that Conrish had just killed and then only partially restored. The “procedure” is intercut with shots of Onslow Stevens overacting, a group of medical scientists watching, and the child oozing about how swell his dad is. All of which makes it worse.

The dialog is exactly what you’d expect from a quickly written propaganda flick. Important moments flash by with a few words, and then we get long speeches, all culminating in the final:

“Dr. Cornish is the man of the hour; Dr. Stone and I are merely contributors to his fulfillment. “

(Kid: “Dad, You’re the swellest dad in the world”)

“Gentleman, what you’ve seen demonstrated is only a forerunner in the march of science. It’s promise to humanity has been answered today. The next step is in the hands of tomorrow.”

Life Returns isn’t horror, except for it’s connection to dog murder. It’s sometimes called science fiction and I suppose that fits since Cornish couldn’t do what is implied in the film. The best label for Life Returns is garbage.