The 1960s

If you’ve missed the explanation for the FOSCARs list, look here.

If you’ve missed the explanation for the FOSCARs list, look here.

My plan for the FOSCARs was to cover the Golden Age of Hollywood, which ended in the 1960s, but like most movements, there was no moment when it ceased to exist. Some put its demise at 1960, but more for convenience than any solid reason. 1969 is also sometimes chosen, although that seems to be pushing it a bit as by then the old studio system was gone, the Hayes code was tossed, distribution and financing had changed, etc. So the end was a slow blur with ’60 clearly in, and ’69 clearly out. If I must choose a year, I’d go with ’63, and I will go at least that far here. Time will determine if I go further.

So, what did the ’60s bring to film? Inconsistency, except that the ’50s were already doing that, so the ’60s just intensified it. Without firm studio hands making sure there was something worth the public’s money at all times, and also reigning in both the best and worst impulses of filmmakers, anything could be made and at any time. So the 1960s are filled with fantastic films and absolute garbage. One year will have multiple masterpieces and be backed up with a stream of great films, and the next will have only middling works. Hollywood was still making magnificent films, but it could no longer be counted on, and foreign cinema took up some of the slack.

As the Golden Age faded away, so did the stars that filled it. Cary Grant had a few more films in him, as did Katherine Hepburn, but it was time for new actors and new directors, taking new chances. And the music changed. “Silver Age” composers drifted away from the romantic music of the studio age, incorporating more jazz and eventually, rock-n-roll. All those new people, new ideas, and new outlooks produced some amazing works, but there is something to say about consistency, and in the end, the decade can’t equal the ’40s or the ’50s.

1960

1961

1962

1963

1964

1965

1966

1967

1968

1969

1960

-

The Magnificent Seven

- Elmer Gantry

- Inherit the Wind

- La Dolce Vita

- Make Mine Mink

- Our Man in Havana

- The Virgin Spring

No year has required me to watch and re-watch and re-re-watch so many films, which has lead me to write more than I normally do. But this is a tricky year. 1960 doesn’t stand out for the heights it attains but for its depth. Besides my seven nominees (my maximum number), there are multiple nominee-worthy films that would have made it in a less jam-packed year, including L’Avventura, Sink the Bismarck!, and Psycho, along with the year’s best F&SF film (![]() ) The Time Machine, and its close rival Village of the Damned. The winner is The Magnificent Seven, a film that both deconstructs the genre and celebrates it.

) The Time Machine, and its close rival Village of the Damned. The winner is The Magnificent Seven, a film that both deconstructs the genre and celebrates it.

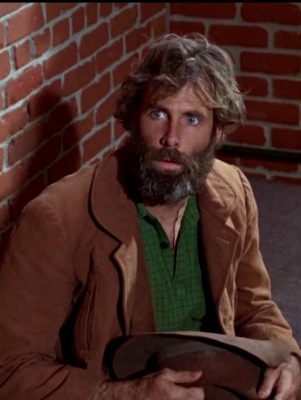

“Only the farmers won. We lost. We always lose.”

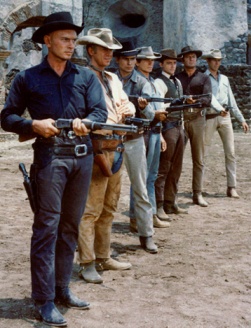

The only option after it was released was to redefine the genre with darker takes like The Wild Bunch and with the Spaghetti Westerns, which, like The Magnificent Seven, were based on the works of Akira Kurosawa. The story follows Kurosawa’s The Seven Samurai closely, though it massively changes the characters. It also drops the Japanese stage acting of the original, and its brand of humor, which Kurosawa would do himself with 1961’s Yojimbo, the father of those Spaghetti Westerns. Sometimes a great performance comes from an actor twisting into a part, and sometimes from the actor perfectly fitting the part. Here we get the second. Yul Brynner, Steve McQueen, Horst Buchholz, Charles Bronson, Robert Vaughn, Brad Dexter, and James Coburn are their characters: larger than life, cool, but with a hint of loneliness. The score takes it to another level. I rank it as the finest of the silver age, and composer Elmer Bernstein is king of the era. It is epic and heroic, yet doesn’t wash away the melancholy. If nothing else had worked, the score alone would make this a good film. But everything else does work.

The other six movies are too close for me to rank, so it’s a six-way tie for 2nd. Elmer Gantry is the most interesting of those six, a film that could not have been made a few years earlier. Our “hero” is a charming cheat and liar, who twists and manipulates all those around him to weasel in on a good and pure evangelist. But the message isn’t one you’d have gotten from old Hollywood. Instead, danger doesn’t come from charlatans, but from true believers. Inherit the Wind also touched on religion in what many found an uncomfortable manner. An adaptation of the play, it is a fictionalized version of the Monkey Trial, filled with great performances by Spencer Tracy, Fredric March, and a non-dancing Gene Kelly.

Previously written reviews save me from carpal tunnel from this entry. La Dolce Vita is an often beautiful tale of existential angst (My review here), Make Mine Mink is a solid Post-War British Comedy (My review here), Our Man in Havana is comedy-thriller-satire (My review here), and The Virgin Spring continues Ingmar Bergman’s examination of a world without God (My review here).

In a year this deep (I list 12 contenders), it is comical that the Academy couldn’t do better than one top choice, that being Elmer Gantry. Their other four were The Apartment, Sons and Lover, The Sundowners, and The Alamo. At first, I felt like giving them some credit for not nominating the uneven, but screaming-for-a-nomination, Spartacus (My review here), but it would have been a huge improvement over Sons and Lovers, The Sundowners, and The Alamo.

Their winner was The Apartment, which, as the second-best nominee, is a kind of success. It’s directed by Billy Wilder, one of my favorite directors, and whose films have been nominated 8 times for FOSCARs, winning 3, including in ’59. But The Apartment isn’t in his top 10. It is, and was, a critical darling, but I don’t buy into it. It’s a satire, but the question is, of what? It’s about a man who loans out his apartment to corporate bigwigs for their affairs in order to get ahead, and about his romance with his boss’s castoff. This would be fine if it left its claws out and didn’t want us to like C.C. Baxter, the wimpy weasel “protagonist,” but the film needs us to sympathize with him. Apparently, Baxter is the nice guy that girls should really go for instead of the wolfish boss, but I find them equally loathsome. It translates particularly poorly to recent times where weak, mealy men are harassing women with their claims of being the “nice guy.” It’s far too close to being an “incels are great” movie, and if you don’t know what that means, keep it that way; your life will be better. This could have been a great biting satire, eviscerating corporate culture, sexist men in power, and the weaker yes-men who enable the whole sleazy operation, but it pulls its punches and settles into being an off-putting romance.

Sons and Lovers is more accurately Sons and Lover Part 2 as the first half of the novel was jettisoned. That may have been a smart move, but it does make the beginning of the film abrupt. There were plenty of these kitchen sink dramas, but this one is the entire movement in one—less a story and more a 98-minute cliché. Perhaps in 1960 this movie could be seen without laughing, but now it’s a parody of itself. At least it’s well-acted, except for Dean Stockwell, who’s outclassed by supporting players Tevor Howard, Wendy Hiller, Ernest Thesiger, and most everyone else. Now (and I’d think in 1960, but certainly now), to pull off the sensitive artist with a clinging, unhappy mother and an alcoholic, coal miner father story you need some subtlety—a script that doesn’t have everyone spouting off exactly how they feel every few minutes would have helped. So…many…speeches… Jack Cardiff is one of the finest cinematographers of all time, but he was a mid-level director, lacking the ability to overcome the cumbersome story.

Slipping even further is The Sundowners, a family outdoor adventure that screams the worst of Disney, but somehow isn’t Disney. Robert Mitchum plays the clichéd foolish man, Deborah Kerr his spirited wife, and along with their perfect son, they travel the Australian countryside. It’s “cute.” Director Fred Zinnemann is mainly concerned with wide scenic shots and sheep. The sidekicks, Glynis John in the Glynis Johns role and Peter Ustinov playing Peter Ustinov, offer some amusement. I suppose in 1960, if you had a few prepubescent children, this would have made a passable family outing to the drive-in, as long as the focus was the popcorn.

Which leads us to The Alamo. It may not be a worse viewing experience than The Sundowners or Sons and Lovers, but it clearly shouldn’t be in on an awards list, something every critic knew at the time. It’s hard to imagine now what kind of power John Wayne had in Hollywood. Or maybe not so hard when I look at a Trump rally. In 1952 he’d managed to derail the politically-charged High Noon’s chances, though he’d lacked the power to get his own starring vehicle to win. In 1960 he had Spartacus to complain about, but his push was to get an Oscar for his red, white & blue, Wayne-directed and starred The Alamo. He couldn’t quite manage that, but he could get his film the nomination that would have gone to Spartacus. He spent a huge amount of money buying his way onto the shortlist for Best Picture, (along with 5 other unworthy nominations, and one reasonable one for Sound), but he couldn’t buy (or cajole with claims that you were unpatriotic if you didn’t support it) enough votes to win a statue. As for the film, it’s bloated, and slow, though in most other ways rises to the level of mediocrity. Sitting next to The Magnificent Seven, it seems childish. Worse films have been nominated, though rarely for worse reasons.

Category FOSCARs:

Director: Ingmar Bergman {The Virgin Spring}

Screenplay: Our Man in Havana

Actor: Alec Guinness {Our Man in Havana}

Actress: Jean Simmons {Elmer Gantry}

Supporting Actor: Laurence Olivier {Spartacus}

Supporting Actress: Shirley Jones {Elmer Gantry} ![]()

Best Ensemble: The Magnificent Seven

Cinematography: The Virgin Spring

Art Direction: L’Avventura

Effects: The Time Machine ![]()

Makeup: William J. Tuttle {The Time Machine}

Choreographer: Hermes Pan {Can-Can}

Score, Non-Musical Film: The Magnificent Seven (Elmer Bernstein)

Song: Never on Sunday {Never on Sunday} ![]()

Musical Routine: The Rumble {Pepe}

Animated Feature: Alakazam the Great

Animated Short: High Note (Chuck Jones/WB)

F&SF Feature: The Time Machine

The best director race is a tight one. I chose Bergman, but it’s a coin flip between him and Hitchcock (Psycho), with Fellini (La Dolce Vita), Wilder (The Apartment), Michelangelo Antonioni (L’Avventura), and Carol Reed (Our Man in Havana) not far behind. Likewise, the Best Actor category is tricky, with Burt Lancaster (Elmer Gantry), Anthony Perkins (Psycho), and Spencer Tracy (Inherit the Wind) all having a claim at the crown, as well as Yule Brynner (The Magnificent Seven) by mere force of will.

Elizabeth Taylor notoriously won the Best Actress Oscar on a sympathy vote after being hospitalized, but no one thinks she deserved it; I’ve corrected that here. The Supporting Actor category is equally notorious. Chill Wills’ aggressive campaign for his so-so work in The Alamo was even more over the top than Wayne’s for the film, taking out full-page ads where he brought up patriotism, prayer, and his personal love and relationship with all the voters. He lost. The winner was Peter Ustinov in Spartacus—a good pick, and the best of those nominated.

It was an exceptionally weak year for dance, which was a side-effect of it being a weak year for musicals. The Best of those was Bells Are Ringing, which has little in the way of dynamic motion, and functions based on the singing (not moving) skills of Judy Holliday. Can-Can and Let’s Make Love are the most significant dance films of the year, and neither broke new ground, with the second containing some straight-up bad choreography. Pepe, a gimmick flick where Cantinflas runs into numerous Hollywood celebrities, pulls the best routine of the year out of thin air. The jazz-ballet The Rumble, danced by Shirley Jones, Michael Callan, and Matt Mattox, is unlike anything else in the picture.

Animated Feature is won by a Japanese musical take on Journey to the West. It isn’t a great work, but the best of what very little is available.

The Oscar for Animated Short went to Munroe, which is my runner-up, and they did nominate High Note, so they didn’t do badly.

1961

-

Breakfast at Tiffany’s

- The Hustler

- Viridiana

- Yojimbo

- West Side Story

After a year with 12 worthy films, 1961 can’t come up with 5. For that 5th slot, I choose West Side Story, though I could have easily selected The Guns of Navarone or The Parent Trap, or hell, even Mysterious Island which snatches up my best F&SF (

After a year with 12 worthy films, 1961 can’t come up with 5. For that 5th slot, I choose West Side Story, though I could have easily selected The Guns of Navarone or The Parent Trap, or hell, even Mysterious Island which snatches up my best F&SF (![]() ) award. But West Side Story occasionally does hit greatness, if only during the dances, so I give it the nod. When characters start talking, things don’t go so well. If they had to cast a white girl as the lead, couldn’t they have gotten one who could sing or dance? Well, at least she was an adequate actress, which puts her one skill up on her co-star. (My review here)

) award. But West Side Story occasionally does hit greatness, if only during the dances, so I give it the nod. When characters start talking, things don’t go so well. If they had to cast a white girl as the lead, couldn’t they have gotten one who could sing or dance? Well, at least she was an adequate actress, which puts her one skill up on her co-star. (My review here)

Of the next three, it’s hard to choose one over the others. Yojimbo is my favorite Akira Kurosawa film. It was also Japan’s favorite, cementing Kurosawa’s position as their greatest filmmaker, and giving Toshiro Mifune the persona he is most remembered for and often would return to. It had a huge impact, including creating the spaghetti Western (Sergio Leone would pay a substantial penalty for his plagiarism in making A Fistful of Dollars) and solidifying the modern version of the nameless antihero. It’s clearly the best photographed of Kurosawa’s films, as well as the tightest; I don’t think he ever had a better-edited film. Whether it is his best film or not is a question calling for its own essay, but I’m willing to give it the nod. Both constructed from, and deconstructing, American Westerns and Noirs, Yojimbo follows the nameless samurai into a hellhole of a town where two crime bosses are at war, and he decides to take them both down. It’s violent, exciting, and funny. People tend to forget that last one. I wouldn’t argue with anyone who called it a comedy.

The Hustler is a sports-melodrama Noir, where the sport doesn’t matter. It has one great performance after another, and great dialog to help those along. It’s a bit long for how bleak it is, but art isn’t always a good time. Viridiana has as dim a philosophy, but it delivers it with dark and twisted humor. The Hustler suggests that in a dark world filled with corrupt people, you can strive to be better. Viridiana says that the world is indeed dark and corrupt, so you might as well enjoy yourself.

The winner is Breakfast At Tiffany’s. It changed film, changed how female characters were written, and has one of the great, iconic performances from Audrey Hepburn (My review).

Considering the limited options, the Academy did OK. Sure, they missed the best film of the year (which was unexpected at the time), and as usual, ignored worthwhile foreign films, but they did nominate The Hustler, and the rest of their choices were sitting in the same pool I was dipping into for my fifth spot: West Side Story (which won the Oscar), The Guns of Navarone, Fanny, and Judgment at Nuremberg.

The Guns of Navarone was part of the string of epic, ensemble war films of the ‘60s. Several of its filmmakers planned to make it an anti-war film, but that doesn’t show in the finished product. Instead, we have a fun, action-packed spy flick that lacks depth but doesn’t really need any. The actors were all too old for their parts (in some cases, far too old) and it has its silly moments toward the end, but generally, this is solid entertainment.

Stanley Kramer followed Elia Kazan as THE message director, and like Kazan, he could make excellent pictures (On the Beach, Inherit the Wind), but just as easily he could swamp a production with ever-growing waves of message. Judgment at Nuremberg doesn’t quite sink from it, but it is sailing pretty low. What works is some great performances from Maximilian Schell, Judy Garland, Werner Klemperer, and perhaps Montgomery Clift (it’s hard to rank it as a performance since Clift was mentally incapacitated and couldn’t remember his lines or focus, so appeared as a convincing mentally incapacitated character who can’t remember what he’s saying and can’t focus), and good enough performances from Richard Widmark and Spencer Tracy. What’s not so good is the excessive runtime, the meandering plot that takes us out of the courtroom for Tracy’s trips around town, the Kramer-admitted questionable camera work, and all those speeches. I’d have liked a more dynamic performance by Tracy, but if you cut an hour of its excessive 3 hours and kept it to the inside of the courtroom, I might have stuck it on my top 5 list too.

Finally there’s Fanny, a romance that bounces from melodrama to comedy. It’s fine for the soap opera set, but beyond that has limited appeal. It’s a shock it works as well as it does, as it’s an adaptation of a Broadway musical (itself based on a trilogy of French films), but without the songs. How many musicals work without the music?

Category FOSCARs:

Director: Akira Kurosawa {Yojimbo}

Screenplay: Breakfast at Tiffany’s

Actor: Paul Newman {The Hustler}

Actress: Audrey Hepburn {Breakfast at Tiffany’s}

Supporting Actor: George C. Scott {The Hustler}

Supporting Actress: Rita Moreno {West Side Story} ![]()

Cinematography: Yojimbo

Art Direction: Yojimbo

Visual Effects: Mysterious Island

Choreographer: Jerome Robbins {West Side Story}

Score, Non-Musical Film: Breakfast at Tiffany’s (Henry Mancini) ![]()

Song: Moon River {Breakfast at Tiffany’s} ![]()

Musical Routine: Prologue {West Side Story}

Animated Short: Nelly’s Folly (Chuck Jones/WB)

Animated Feature: One Hundred and One Dalmatians

F&SF Feature: Mysterious Island

Sophia Loren won the Actress Oscar for Two Women (not eligible for me as it was released in 1960) for a worthwhile performance, though its legacy is that it was the first time Best Actress went for a foreign language performance. I place the nominated Hepburn easily ahead. Newman was nominated for Best Actor, but lost out to Maximilian Schell, who took the crown due to a very commanding speech in Judgment at Nuremberg. For me the clear winner is Newman. The real fight for the FOSCARs was in Supporting Actor, with The Hustler providing two magnificent performances (Jackie Gleason’s being the other); the Oscar went to George Chakiris for West Side Story; his nomination was deserved, but The Hustler supplied too many great performances to leave room for anyone else. The rest of the FOSCARs is pretty clear cut, varying from the Oscars mainly due to the latter paying only minimal attention to foreign films, thus nominating Yojimbo only for costuming.

The weakest year for animated shorts in over a decade. Studios were closing down their theatrical short film departments as TV was taking over, which is where Jones would move soon.

1962

-

Lawrence of Arabia

- Advise & Consent

- The Exterminating Angel

- The Manchurian Candidate

- The Music Man

Without Lawrence of Arabia, 1962 would be a solid year. The Manchurian Candidate would make for a good winner; a chilling political thriller that kept me glued to the screen, it would sit comfortably with the winners of the previous few years. The Music Man is a first-class musical, one of the best Broadway-to-film adaptations. Advise & Consent is another political thriller, but a bit lighter and more melodramatic, filled with excellent performances. And The Exterminating Angel fills in the foreign film/art film slot, while also taking my best F&SF award (My review here). So 1962 is a nice, above-average year.

Without Lawrence of Arabia, 1962 would be a solid year. The Manchurian Candidate would make for a good winner; a chilling political thriller that kept me glued to the screen, it would sit comfortably with the winners of the previous few years. The Music Man is a first-class musical, one of the best Broadway-to-film adaptations. Advise & Consent is another political thriller, but a bit lighter and more melodramatic, filled with excellent performances. And The Exterminating Angel fills in the foreign film/art film slot, while also taking my best F&SF award (My review here). So 1962 is a nice, above-average year.

And then we add Lawrence of Arabia.

Four great films, and they fade out of the conversation when it is added in. Lawrence of Arabia is one of the top 10 films of all time. It’s what the word masterpiece is for. (My thoughts on it here).

And the Academy didn’t blow it. For the 3rd time in its history, they picked the right winner, and gave it 6 other statues. Lawrence of Arabia stood so far above everything even they couldn’t ignore it. They also nominated The Music Man. Their final three were To Kill a Mockingbird, The Longest Day, and Mutiny on the Bounty. To Kill a Mockingbird is much loved, though not by me. I wasn’t fond of the book, which was a middling-written, middle-grade novel, though with an important social message. The film has the flaws of the book but adds to it a sense of reality that obscures that we are seeing things through the rose-colored glasses of a child. Many people like the movie because they hero-worship Atticus Finch, apparently missing that he isn’t actually the way he appears (the sequel novel, released many years later, made that very clear, and people were not happy about it). The 4th nom was The Longest Day, a reasonably enjoyable all-star war film where a majority of those stars didn’t bother even attempting characters beyond their Hollywood personas (John Wayne as John Wayne is particularly annoying). It’s the weakest of these sorts of films that were popular in the ‘60s. Finally, there’s Mutiny on the Bounty, which can’t live up to its 1935 predecessor. It seems bizarre now that they missed The Manchurian Candidate, but they picked the right winner, so I’ll let them off the hook.

Category FOSCARs:

Director: David Lean {Lawrence of Arabia} ![]()

Screenplay: Lawrence of Arabia

Actor: Peter O’Toole {Lawrence of Arabia}

Actress: Anne Bancroft {The Miracle Worker}

Supporting Actor: Omar Sharif {Lawrence of Arabia}

Supporting Actress: Angela Lansbury {The Manchurian Candidate}

Cinematography: Lawrence of Arabia (Freddie Young) ![]()

Art Direction: Lawrence of Arabia ![]()

Editing: Lawrence of Arabia ![]()

Score, Non-Musical Film: Lawrence of Arabia (Maurice Jarre) ![]()

Song: Paris is a Lonely Town {Gay Purr-ee}

Animated Short: Icarus Montgolfier Wright (Jules Engel)

Animated Feature: {Gay Purr-ee}

F&SF Feature: The Exterminating Angel

I almost feel sorry for anyone competing against Lawrence of Arabia. All Night Long has a wonderful soundtrack, filled with great jazz musicians (including Dave Brubeck), but even it can’t break the stranglehold. Lawrence of Arabia only loses where it doesn’t compete (as in the actresses categories as it has no female speaking parts).

The Academy nominated, but did not give the award to Lawrence of Arabia for Actor, Supporting Actor, and screenplay. I have corrected that. O’Toole’s is one of the greatest ever performances. Sharif’s Oscar loss is generally felt not to have been to a performance, but rather one of the last chance career awards that the Academy does so often, this time for Ed Begley. After Sharif there are four more from Lawrence of Arabia (Alec Guinness, Jack Hawkins, Claude Rains, Arthur Kennedy) I’d go to before moving to Charles Laughton for Advise & Consent.

The Animated Short category fell even farther such that I almost didn’t choose any winner. Icarus Montgolfier Wright is a reading of a Ray Bradbury story over some semi-animated illustrations. It makes it in purely due to the story, which is better still if read. The Animated Feature is as weak, and wins due to being better than Arabian Nights: The Adventures of Sinbad, a Japanese kits TV series cut down to feature-length.

1963

-

The Servant

- Bluebeard’s Castle

- Charade

- The Great Escape

- Ladies Who Do

1963 is one of the weakest cinematic years of all time, lacking both in quality and quantity. It’s a year where “very good” is uncommon, and I question if “great” should ever be used. Hollywood was particularly lacking, leaving it to the English, but this wasn’t 1949 when they could save the day; making it passable is all they could manage. The best the year has to offer is a strange British film: The Servant. It’s a fascinating work that rips into the class system and is thought to have changed the type of films made in England (My Review here). The Brits also supplied Ladies Who Do, the last of the Post-War British Comedies. It’s a fun satire, and worthy of a nominations, but it doesn’t make my top 10 list for that movement. (My review here)

1963 is one of the weakest cinematic years of all time, lacking both in quality and quantity. It’s a year where “very good” is uncommon, and I question if “great” should ever be used. Hollywood was particularly lacking, leaving it to the English, but this wasn’t 1949 when they could save the day; making it passable is all they could manage. The best the year has to offer is a strange British film: The Servant. It’s a fascinating work that rips into the class system and is thought to have changed the type of films made in England (My Review here). The Brits also supplied Ladies Who Do, the last of the Post-War British Comedies. It’s a fun satire, and worthy of a nominations, but it doesn’t make my top 10 list for that movement. (My review here)

The best of Hollywood was Charade, a light thriller-romance with a definite Hitchcock feel. Audrey Hepburn is delightful as the innocent tossed into danger, Cary Grant is Cary Grant, and the whole thing is a lot of fun. Two years earlier Hepburn had also been delightful in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, the best film of her career. This is her sixth-best, and there is a lot of space between first and sixth. After that comes The Great Escape—one of those “toss a huge cast in to lure people away from their TVs” type films that filled the 1960s. The characters are identifiable if not developed, though the accents are…interesting. Steve McQueen’s demands that he be made to look more heroic didn’t help the picture (director John Sturges wanted to dump him, but the studio was counting on McQueen to sell tickets, so overrode him), nor does making the German’s idiots, but it has some exciting moments and some funny ones. It’s “very good,” and I’d be comfortable with it being a finalist if it ended up in 7th.

And that’s it. Nothing else released to theaters was good enough to compete. So for my 5th nominee, I went to German TV. Bluebeard’s Castle (or Herzog Blaubarts Burg} is a filmed version of the two-person opera, made by master British director Michael Powell, with a major assist by production designer Hein Heckroth, who he’d worked with many times before, including on The Red Shoes and The Tales of Hoffmann. It’s a low budget affair, but captivating, with amazing sets. It’s a fitting farewell to one of the greatest filmmakers of all time (Powell made 3 lesser films after this), and I was tempted to put it in first place. It’s hard to compare it to the theatrical features; it’s such a different kind of work. So, I’ll call it a very close second.

The Academy chose nothing that should have gotten a nomination, but it isn’t as if they had much to choose from (they weren’t going to choose either a weird, homoerotic, British film or a Britcom, so that eliminated the year’s best). They took Cleopatra, How the West Was Won, America, America, Lilies of the Field, and Tom Jones. Without quality to pave the way, it was money that got nominations (well, that usually is the determining factor), thus the uneven and bloated Cleopatra got a nom; it had the biggest box office for the year, though it still managed to lose money. It’s often considered to be one of the worst Best Picture nominations, though I think that’s too harsh. It’s not a good film, but I’d rather sit through its silliness than several of the other nominees. The second-biggest moneymaker was How the West Was Won, a movie that was made purely to fight TV, with no concern for artistry or even skill. It was big, it was long, it had a lot of often miscast stars (but it did have a lot of them, and quantity was what mattered), it had what could politely be called an inconsistent script, and it had one of the dumbest gimmicks ever: Cinerama. Three lenses were required to shoot a scene, and three projectors were needed to show it on a curved screen. I’m sure there’s some fun uses for this (perhaps nature films), but a narrative isn’t one of them. When you position your actors in the frame not based on what’s needed for the story, but what works for those lenses, you’re in trouble.

Beyond money, there was the normal rewarding of Academy favorites, no matter the film, thus the nomination of America, America. Director/writer/producer/nephew Elia Kazan’s filmmaking had switched from social messages to himself. His self-indulgence reached new levels with this 3-hour film about his uncle’s quest to come to America. He was KAZAN (and not a traitorous sellout, or so he kept telling himself in whatever medium he could—Dude, you named names to the House Un-American Activities Committee; accept what you did and move on with your life), so what did he need with trained actors? What did he need with normal human behavior when his characters could suddenly scream? What did he need with editing? Audiences didn’t like the result, nor do I.

Lilies of the Field answers the question, “What can we do with a handsome Black actor that won’t scare White American culture?” Make him a laborer for nuns. It’s family-friendly, religion-friendly, and sex-free. It’s well made across the board, making it one of the better nominees.

And finally, the Oscar winner was Tom Jones, which, considering what it was up against… Sure. Why not? At least the British cast was good. It tries to get by on being edgy and a little naughty, and it isn’t either. The novel was both of those things, but then it was published in 1749. Edgy for 1749 and 1963 are not the same thing. So it ends up being mildly amusing (very mildly) instead of funny, and a mildly good film.

Category FOSCARs:

Director: Alfred Hitchock {The Birds}

Screenplay: The Servant

Actor: Dirk Bogarde {The Servant}

Actress: Audrey Hepburn {Charade}

Supporting Actor: Robert Morley {Ladies Who Do}

Supporting Actress: Wendy Hiller {Toys in the Attic}

Cinematography: The Servant (Douglas Slocombe)

Art Direction: Bluebeard’s Castle (Hein Heckroth)

Visual Effects: Jason and the Argonauts (Ray Harryhausen)

Score, Non-Musical Film: The Pink Panther

Song: Call Me Irresponsible {Papa’s Delicate Condition}

Animated Short: The Critic (Ernest Pintoff) ![]()

Animated Feature: The Sword in the Stone

F&SF Feature: Bluebeard’s Castle

The Pink Panther was released late enough in December that it is often considered a 1964 film. If I were to go with that, From Russia With Love and The Great Escape are in the wings for best score, so it was at least a good year for music. The Supporting Actor category is a little awkward. Morley could be called the male lead in Ladies Who Do, though I think it’s a case of no male lead, and everyone supporting the formidable Peggy Mount. My second choice would be James Fox from The Servant, but he’s more of a co-lead.

The Critic won the Oscar for animated short, and I’m agreeing, but only because there’s nothing else. It’s a brief Mel Brooks-written joke.

Bluebeard’s Castle takes best F&SF (![]() ), beating out Jason and the Argonauts (My review), which was in contention purely due to Ray Harryhousen’s special effects.

), beating out Jason and the Argonauts (My review), which was in contention purely due to Ray Harryhousen’s special effects.

1964

-

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

- The Americanization of Emily

- Goldfinger

- Kwaidan

- Mary Poppins

- The Umbrellas of Cherbourg

- Zulu

After one of the weakest years in film history, we get one of the strongest. 1964 has both strength at the top and volume. It doesn’t just have 7 films worthy of nomination, but 12 great films, the additional ones being:

After one of the weakest years in film history, we get one of the strongest. 1964 has both strength at the top and volume. It doesn’t just have 7 films worthy of nomination, but 12 great films, the additional ones being:

Onibaba

Robin and the 7 Hoods

Seven Days in May

A Shot in the Dark

Woman in the Dunes

Plus it has a pool of near-greats that wouldn’t be embarrassing on the nom list in a weaker year, including My Fair Lady, Fail-Safe, and The Best Man (which might be higher if it didn’t repeat so much of Advise & Consent from ‘62).

And what about those 7? Dr. Strangelove is a satiric masterwork, with a biting, hilarious script and multiple career-best performances. It’s arguably Stanley Kubrick’s finest film, the best film of the year, and the 2nd best of the 1960s (you just can’t get around Lawrence of Arabia). The beguiling Mary Poppins is filled with beautiful and catchy songs, gorgeous cinematography and art design, and spectacular performances. It’s a family film that works wonderfully for kids and then works as well in a slightly different way for adults. It’s the 2nd best film of the year and the 4th best of the 1960s. Then comes Zulu, an exciting, thoughtful, violent and yet beautiful war picture, with an amazing score, battle scenes filled with actual Zulu warriors, and fantastic performances, and it’s the 3rd best film of the year and the 5th best film of the 1960s. Zulu, the 3rd best film of the year, would win in 7 of the 10 years of the decade. That’s one hell of a strong top 3.

And things don’t fall far after those. The remaining 4 are all great films in the same league as the movie that wins most years. Kwaidan is a three hour, four-part Japanese anthology film made up of period ghost fables. Reality is not the goal, but beauty is at least one of several goals as the whole thing is ridiculously gorgeous. It’s mesmerizing, which at three hours, it needs to be. The Americanization of Emily is another satire on war and politics, with the second top-notch performance by Julie Andrews in the year, and one of James Garner’s best. It was directed by Arthur Hiller, but it’s really screenwriter Paddy Chayefsky’s film, and it won’t be the last time we hear from him.

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg is a French operetta that made Catherine Deneuve a star. The score is jazzy and moving, the story is romantic and sad and uplifting, and the colors are vivid. And we finish with one of the best James Bond pictures, one that earns it spot. Goldfinger is a great action film; it’s well-paced, exciting, and clever, with a great score and memorable theme song.

While they didn’t give it the Best Picture Oscar, it’s shocking that the Academy even nominated Dr. Strangelove, both because it is the best film of the year—if you’ve been reading my FOSCARs, you know how rarely that happens—and because it’s a twisted film that takes a negative stance on the U.S. They also nominated Mary Poppins, which is less odd, but still notable. Then they added the Oscar-bait Becket. Becket should be a great film, with Peter O’Toole who’d recently completed one of the greatest performances of all time with Lawrence of Arabia, and Richard Burton, who could be a bit stiff (and was here) but owned that magnificent voice, in a successful play that would allow them to really go at each other. But it’s bland. It isn’t bad, but it’s disappointing. The sets and costumes are nice, but the cinematography isn’t good enough to make it beautiful. I put the blame on part-time film director Peter Glenville, who wasn’t up to the job of a large scale movie. The fourth nominee was Zorba the Greek, an OK film, that no one seems that enthralled with and no one now thinks should have been in the race. It’s too long, too slow, too random, but OK.

The final nominee was the other big gun, My Fair Lady. It was the second-biggest money-maker of the year and exactly the kind of film the Academy likes to reward, and they did. It’s a good film, approaching very good. But in a year like 1964, very good shouldn’t have been enough to win awards. (My review here)

Category FOSCARs:

Director: Cy Endfield {Zulu}

Screenplay: Dr. Strangelove

Actor: Peter Sellers {Dr. Strangelove}

Actress: Julie Andrews {Mary Poppins} ![]()

Supporting Actor: George C. Scott {Dr. Strangelove}

Supporting Actress: Anne Vernon {The Umbrellas of Cherbourg}

Cinematography: Zulu

Art Design: Mary Poppins

Effects: Mary Poppins ![]()

Makeup: William J. Tuttle {7 Faces of Dr. Lao}

Score, Non-Musical Film: Goldfinger

Song: Feed the Birds {Mary Poppins}

Musical Routine: Step in Time {Mary Poppins}

Animated Short: The Pink Phink (DePatie-Freleng) ![]()

F&SF Feature: Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

It was a top year in every way, perhaps best demonstrated by music. For Song, this is the best year since the 1930s, and possibly the best year ever (since rarely had older film musicals had all new songs written for them), with every song in Mary Poppins, multiple songs from A Hard Day’s Night, My Kind of Town from Robin and the 7 Hoods, and the title track from Goldfinger all being worthy of winning. My choice for best song of the year has always been from Mary Poppins but has changed with age. As a kid, it was Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious, in my twenties it was Chim Chim Cher-ee (which won the Oscar), and in my forties, it switched to Let’s Go Fly a Kite. I’m now in my fifties, and now it’s Feed the Birds.

The entire theatrical animated shorts business had collapsed. The Pink Panther, based on the title sequence of the movie of the same name, took over as the premier animated character. His cartoons drifted to mediocrity quickly, but this first outing was very good.

1965

-

It Happened Here

- Battle of the Bulge

- King Rat

- The Loved One

- The Spy Who Came in From the Cold

It’s another exceptionally weak year, but unlike ’63, it at least has 5 legitimate nominees, even if they tend toward the lesser edge of nominees. After the heights of ’64, it’s a prodigious drop.

It’s another exceptionally weak year, but unlike ’63, it at least has 5 legitimate nominees, even if they tend toward the lesser edge of nominees. After the heights of ’64, it’s a prodigious drop.

But 1965 does have a fascinating winner, a micro-budget indie, started by two teenagers in 1956 and finished eight years later. It Happened Here is a mesmerizing alt-history film, letting us experience a Nazi-controlled Britain. It was controversial on its release (Brits didn’t like the suggestion that anyone English could ever be a collaborator), but it’s lauded now by those who have seen it. But too few have, and as a film that has a lot to say about our times, everyone should. (My review).

Coming in second is King Rat, a cynical POW movie. Like Stalag 17, the lead is a hustler that deals with the enemy and cares little about the other prisoners. Unlike it, there’s no humor here. George Segal’s King has never had it so good and likes being in the camp where he’s important. Yet he’s more likable than the Brit who wants to pull him down, as he too is not motivated by anything noble, but simply by hatred. It’s well shot, has a strong message, and the best acting of the year.

Battle of the Bulge is one of the sprawling, epic, fun war films (not like King Rat) that filled the 1960s. It isn’t accurate, but it’s entertaining. Classify it as an action film filled with sweeping battle scenes and wild heroics. There’s lots of shooting and explosions and tanks driving through buildings, yet it manages to create identifiable characters on both sides. Henry Fonda and Telly Savalas control the screen on the American side, but Robert Shaw is the real standout as the German general who prefers war to peace. It’s the exact opposite of the next nominee, The Spy Who Came in From the Cold, which is slow, dark, and depressing, a spy movie with no action, no heroics, and no hope. It was filmed in B&W and mostly in interiors. Richard Burton (my #2 Best Actor for the year) stars as an unlikable spy surrounded by more unlikable spies in a terrible situation that can only end tragically. It’s powerful, but not fun.

Finally just slipping in is The Loved One, a satire of the American funeral institution, the film industry, religion, and British ex-pats. It was advertised as having something to offend everyone, and it does. A good deal of tightening, and different cinematography that complimented the story (it’s washed out, when dark shadows, or perhaps rich colors would have served it better) would have raised it a notch in the ranking.

As for the Oscars, three years after Lawrence of Arabia I’d have expected Doctor Zhivago to take it all. But Zhivago is no Lawrence, and important critics saw that (Pauline Kael called it “stately, respectable, and dead”). Director David Lean was one of the greatest craftsmen and he could be a great artist, and the craft in Doctor Zhivago is, in most ways, top-notch. It’s the artistry that is in question. Zhivago is a slow, plodding, sloshy romance with little plot, filled with shallow or unformed characters. And why wouldn’t it be? Lean was far more interested in the look of the flowers and the falling snow than in the story or the characters. With Lawrence he was interested in everything. Here he wanted to express the romance with the flowers, not the characters, as his intention was to make a poem. A romance needs characters to be compelling, and a plot to allow the characters to act. Doctor Zhivago flopped at first, but the soundtrack was a hit, and the music slowly dragged in the crowds. In the end it made good money, enough to guarantee an Oscar nom, but the negative critical response precluded it from winning.

Darling didn’t have much of a chance, but it’s relatively well thought of today by those who remember it. It’s a very ‘60s film that was nominated for being very ‘60s while stating that no one was happy with changing times. It follows an immoral, superficial model and her immoral, superficial acquaintances as they lie to each other and themselves. It’s exactly what a conservative group would nominate to show how open they are. If Darling had little chance, A Thousand Clowns and Ship of Fools never had any. The first is another very ‘60s film that’s an establishment look at non-conformity, while the second is a disaster movie on a boat, except there’s no disaster and the stars overact even more than expected. Neither has aged well.

The battle was over before it began; The Sound of Music won. I grew up on musicals, and love them, but not The Sound of Music. Of the works of Rodgers and Hammerstein, The Sound of Music lacks the emotional depth of Carousel, the message of South Pacific, the characters of Oklahoma!, and has weaker songs than all of those plus The King and I. And the movie makes everything a little worse. It’s even more sickeningly sweet, it’s slow with terrible editing, the acting is appalling in many cases, and “opening it up” adds nothing but a big, pointless shot of mountains. Julie Andrews holds her own, but it really doesn’t show off her talents. Even with its weak songs, the songs are still the best part. Of the big Broadway musical films of the 1950s through 1970s, this is the worst.

But as the Oscars are political, there wasn’t anything else that could happen. They wouldn’t have awarded a low-budget alt-reality film, and besides, It happened Here wouldn’t be eligible for decades when it finally was shown in LA. King Rat was a failure, and Hollywood does not like rewarding its failures. It was before it’s time. US audiences were still looking only for heroic war pictures. That would imply Battle of the Bulge should have had a chance as it’s all about heroics, but it beat a similar film into production, causing that project to be canceled. Columbia Pictures was not amused, nor were the multiple big-name stars who were out of a job (saving us from John Wayne as Patton), nor Dwight D. Eisenhower who was to be an adviser. The Spy Who Came in From the Cold was non-heroic and disparaging of Western foreign policy—acting was the only statue it could have won (and it didn’t). As for The Loved One, most everyone found it offensive, which is no way to win awards. So The Sound of Music it was.

Category FOSCARs:

Director: Bryan Forbes {King Rat}

Screenplay: King Rat

Actor: George Segal {King Rat}

Actress: Pauline Murray {It Happened Here}

Supporting Actor: Tom Courteney {King Rat}

Supporting Actress: Claire Bloom {The Spy Who Came in From the Cold}

Cinematography: Doctor Zhivago (Freddie Young) ![]()

Art Design: Chimes at Midnight

Effects: Battle of the Bulge

Makeup: Doctor Zhivago

Score, Non-Musical Film: The Pawnbroker (Quincy Jones)

Song: Ticket to Ride {Help}

Animated Feature: West and Soda

Animated Short: A Charlie Brown Christmas (Bil Melendez)

F&SF Feature: It happened Here

At least the year wasn’t subpar in all respects, with some great looking films. Besides the flowers of Doctor Zhivago and unlikely castles of Chimes at Midnight, there’s the colorful dreamscape of Juliet of the Spirits, which takes second in Art Design. And the Supporting Actor race was tight; a very close second was Edward G. Robinson for The Cincinnati Kid. Pauline Murray gets Best Actress not for her versatility but by being completely natural.

I hate not giving top song to The Ballad of Cat Ballou, but my enjoyment of the song may not equal its quality.

West and Soda is an Italian parody of spaghetti Westerns. With nothing from Disney, its competition was cheap productions meant for TV and lesser foreign-language movies, such as the Japanese Gulliver’s Travels Beyond the Moon and a Belgian Smurf flick.

Am I cheating for best Animated short? A Charlie Brown Christmas wasn’t released to theaters, but to television. But I already opened those floodgates with Bluebeard’s Castle so I’m not going to worry about distribution methods. It wasn’t an episode of a series, but a complete-in-itself short film, so that counts for me. And it’s a wonderful short, far and away the best of the year.

The Beach movie craze was dying, but for this year, the dregs of that movement ruled the drive-ins, so there’s no qualifying choreography. I’d dropped both Choreographer and Musical Routine for the year.

1966

-

The Russians Are Coming the Russians Are Coming

- Alfie

- How to Steal a Million

- Our Man Flint

- Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

An improvement over ‘65, 1966 is still a weak cinematic year, sitting definitively above only five previous years: 1930, 1932, 1958, 1963, and 1965. It’s not surprising. The studio system was dead and it wasn’t clear who was in charge. Distribution was still confusing, and producers were attempting various mostly shabby tricks to compete with TV. The MPAA had been without a president for three years; Jack Valenti took over in ’66, and he was planning on dropping the old code and replacing it with a rating system (which would happen two years later), so no one knew what was allowed. Chaos isn’t the best environment for filmmaking.

An improvement over ‘65, 1966 is still a weak cinematic year, sitting definitively above only five previous years: 1930, 1932, 1958, 1963, and 1965. It’s not surprising. The studio system was dead and it wasn’t clear who was in charge. Distribution was still confusing, and producers were attempting various mostly shabby tricks to compete with TV. The MPAA had been without a president for three years; Jack Valenti took over in ’66, and he was planning on dropping the old code and replacing it with a rating system (which would happen two years later), so no one knew what was allowed. Chaos isn’t the best environment for filmmaking.

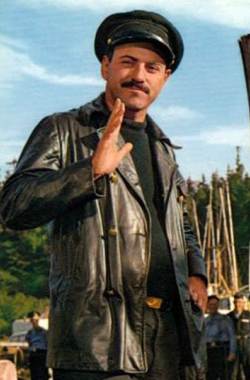

Into this environment comes The Russians Are Coming the Russians Are Coming, and I’m shocked it ended up as the best of the year. I’ve known and loved it since I saw it as a child in ‘66, but this sort of zany comedy rarely ends up on top. However, I’m not the only one who noticed it; it was nominated for an Oscar and won the Golden Globe. A hit in America, as well as receiving a positive reaction in the Kremlin, it had a notable effect on how people in the US viewed those in the USSR, and vice-versa. The story follows a group of Soviet sailors sent ashore onto an isolated US island, searching for a boat to pull their submarine off of a sandbar while avoiding being shot by the islanders who are getting more and more panicked. The film is filled with characters who are simultaneously likable and annoying, played by many of the best comics of the age, but Alan Arkin, in his first major role, steals the movie as the long-suffering second-in-command of the sub. The point is made and the scripted jokes are funny, but this is Arkin’s show.

How to Steal a Million takes 2nd. It’s a romantic comedy/heist pic; it may lack in message, but it has laughs and emotion in abundance. The script is witty, but better is the chemistry created by Peter O’Toole and Audrey Hepburn, ranking as 3rd best in each of their filmographies.

Following it is Our Man Flint, the best of the super-spy parodies. Was anyone ever cooler than James Coburn? It’s like watching a version of Steve McQueen who can act and doesn’t give a damn what you think. His Derek Flint is the ultimate American hero, as Bond is the ultimate British one, possessing every attribute American’s treasure, particularly the ones we don’t want people having in real life. Unlike the other popular parodies of the time, this one cared about the character. It’s funny and exciting.

Alfie made Michael Cane a star, playing the titular, lower-class, self-deluded womanizer. The film stands out for breaking the fourth wall as Alfie explains his feelings directly to the audience. He’s an unreliable narrator, generally trying to make himself sound like what he considers cool, which is worse than what he actually is. It’s a thoughtful and emotional film that pushed censorship rules. I could have done without the theme song that was added to the end titles after its initial release.

Finally, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? could have, and almost was, the masterpiece the year needed. The script nearly matches the play and the play is excellent. And the acting from Richard Burton, Elizabeth Taylor, George Segal, and Sandy Dennis is superb, with minor important exceptions. The cinematography is a detriment (apparently no one knew how to work in dim lighting), but only a small detriment. The problems that count, and they are large, come from deviations from the play. The story takes place in one house, but director Mike Nichols and company felt the need to “open it up,” having the four characters run out in the middle of the night, go dancing, and wander a bit before going right back to where they started. It interrupts the momentum, and this is a film that needed that momentum. Displacing several important discussions change their meanings. And in a film with non-stop great acting moments, I cannot figure why anyone thought both Taylor and Burton needed a pair of overly theatrical ACTING speeches. They had the winner here, but they blew it with a few poor decisions, though it still ends up as one of the top 5 for the year.

I agreed with The Academy more than usual, sharing three nominations: Alfie, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, and my winner The Russians Are Coming the Russians Are Coming. Their fourth nominee was The Sand Pebbles, which is…long. Very long. Very, very long. It’s also slow and depressing. Its anti-Vietnam message (the film uses an earlier Asian conflict) gets muddled and becomes “the Orient is inexplicable and dangerous; let’s just blow it up.” It’s well made, and particularly well shot, but generally considered a film that didn’t deserve its best picture nom.

The Oscar winner was the heavy favorite going in: A Man For All Seasons. It’s exactly the sort of picture they like to award, and why the Oscars are usually wrong. It’s not a bad film, but it isn’t a great one either (My review).

Category FOSCARs:

Director: Lewis Gilbert {Alfie}

Screenplay: Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

Actor: Alan Arkin {The Russians Are Coming the Russians Are Coming}

Actress: Venessa Redgrave {Morgan! A Suitable Case for Treatment}

Supporting Actor: George Segal {Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?}

Supporting Actress: Sandy Dennis {Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?} ![]()

Cinematography: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (Tonino delli Colli)

Art Design: Fantastic Voyage ![]()

Effects: Fantastic Voyage ![]()

Score, Non-Musical Film: Our Man Flint (Jerry Goldsmith)

Song: Georgy Girl {Georgy Girl}

Animated Short: How the Grinch Stole Christmas (Chuck Jones & Ben Washam)

F&SF Feature: Our Man Flint

The weakness of the year shown through in multiple categories, including direction, which was lackluster, cinematography, with major films improperly lit, and art design, which was simply boring. Besides score, it was the acting categories that excelled. The best actor race was the strongest; Michael Caine {Alfie} took 2nd, with Richard Burton {Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?} in 3rd. Peter O’Toole {How to Steal a Million} and David Hemmings {Blowup} would have been solid nominees as well. For Actress, I’d have been happy to have Audrey Hepburn {How to Steal a Million} win for a hypnotically charming performance, but there’s no way around Venessa Redgrave, who’d also took 3rd with her performance in {Blowup}.

For the second year in a row, a TV special is the best Animated Short. It’s also the return of Chuck Jones who dominated this category for over a decade and a half. In second place is It’s the Great Pumpkin Charlie Brown, another fantastic television special.

Is Our Man Flint science fiction? It’s a parody of James Bond, and in general parlance, James Bond is tagged as a “super spy” and action/adventure, not science fiction. But Bond is filled with futuristic gadgets, and Our Man Flint leans into those, with super-science weather control, mind control, and various advanced toys, so yes, it counts, even if it lacks space ships.

1967

-

The Graduate

- How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying

- In the Heat of the Night

- Quatermass and the Pit

- The Young Girls of Rochefort

In 1967, Hollywood started putting the pieces in place. After two of the weakest years ever and nearly a decade of confusion, the film industry was figuring out how to finance films outside of the old studio system, how to compete with television, and how to integrate European trends. The limits of the new freedoms were still hazy, but enough was nailed down so that those freedoms could be used artistically and commercially. And with a film like The Graduate, it’s clear that Hollywood finally understood that the 1950s were gone and that society, and film, had changed.

In 1967, Hollywood started putting the pieces in place. After two of the weakest years ever and nearly a decade of confusion, the film industry was figuring out how to finance films outside of the old studio system, how to compete with television, and how to integrate European trends. The limits of the new freedoms were still hazy, but enough was nailed down so that those freedoms could be used artistically and commercially. And with a film like The Graduate, it’s clear that Hollywood finally understood that the 1950s were gone and that society, and film, had changed.

The late ‘50s were filled with youthful rebellion films. But The Graduate isn’t one of those. Ben isn’t rebelling against anything. It’s been called a counterculture film, but it isn’t. Ben isn’t against anything, but more importantly, Ben isn’t for anything. He’s just lost, and he’s going to stay lost. He’s alienated and the only way out, for a time, is madness, which not surprisingly, doesn’t help. An insane obsession with Elaine drives him to action; he finally does something. But it’s a meaningless obsession; succeeding will achieve nothing, and he’ll find he’s back where he began. Ben’s not a hero. He doesn’t save Elaine, or help himself, or take one positive action in the film. For a time you can be fooled into thinking that The Graduate is building to an exciting, happy climax, but this isn’t a stupid film, and director Mike Nichols and company have made it clear that can’t happen. But he leads you that way, up that rocky but beautiful mountain, until those last 30 seconds. Then anyone who didn’t get it until then falls off a cliff. Elaine yelled out that it wasn’t too late for her, but of course, it was. It’s always too late. Only one character in the film understands the world and has found a place in it, and that’s Mrs. Robinson. And that place is nowhere, but with distractions so that for a time she doesn’t have to dwell on it. This is a brilliantly written film, seeped in existential philosophy, wonderfully portrayed, and is technically superb. It’s also nihilistic and bleak. Sure, it’s called a comedy, but the jokes on you if you think anything will work out.

In the Heat of the Night is another sign of changing times. Its gritty style makes it more kin to ‘70s crime thrillers than those of the studio years. There’s no magic transformation of the characters. While the mystery is a riveting one, it’s eclipsed by the social story. In a racist town, a Black homicide detective, who was just passing through, is pressured into helping with the investigation. While other films of the time have lost their edge, this one still has power. It has numerous compelling moments involving characters that are complexly drawn. Yes, most of the characters are horrible, but they aren’t simple stereotypes. Sidney Poitier was a star, but he’d generally stuck to playing roles that were safe for White audiences, that of the noble, calm Black man. Here, he’s angry and sick of being pushed around. His slapping the bigoted plantation owner is probably the best cinematic moment of 1967.

Those two are followed by a pair of musicals that couldn’t be more different: How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying (My review) and The Young Girls of Rochefort (My review). And finally comes my pick for the best F&SF film of the year, Quatermass and the Pit, re-titled Five Million Years to Earth in the USA (My review). I cut my nominees at 5 as I think that best celebrates the year, though there are multiple films that fit my minimum criteria and would have gotten nominated in ’65 or ’66: Barefoot in the Park, The Dirty Dozen, Fitzwilly, The Jungle Book, and In Like Flint

The Academy and I agreed on two nominees: In the Heat of the Night and The Graduate, though they switched their order. I won’t argue with their choice for the top position since it is one of the better choices in Oscar history.

Their third nominee was Bonnie & Clyde, which has grown in stature over the years, and is nearly as innovative as The Graduate, particularly in incorporating European styles. It was built around (and sold on) its shocking moments, which were intended to propel the film forward. Without those shocking moments, it sags, and the illusion that it’s about something important fades. The problem is, it isn’t shocking. Perhaps it was in ’67, though I didn’t find it so when I first saw it in the early ‘70s and it certainly isn’t now. Some films can keep that power: Freaks, Congo, even The Producers. But not this. As I wasn’t shocked, I could more easily see the experiments that failed (such as the changing film grade), which leaves it a more important film than a great one.

Then there are two things that don’t belong, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner and Doctor Dolittle, two films deeply stuck in the ‘50s. Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner has acting that ranges from good (Sidney Poitier) through unbelievable (Katharine Houghton), to they were just happy he got the words out before dying (Spencer Tracy). The racial politics and White safety (he’s polite, a doctor, handsome, and submissive!) might have been impactful a decade earlier but by ’67 it was embarrassing. It’s the Greenbook of its day. But Tracy had died, Katharine Hepburn was respected, and the message probably did feel weighty to some of the very old members of the Academy, so they gave it a nomination. As for Doctor Dolittle, it’s a weak, poorly conceived and executed children’s film that few children really like, and that’s a nice assessment. I’ve seen others claim that it is the worst best picture nominee of all time. Either way, it doesn’t deserve to be on the list.

Category FOSCARs:

Director: Mike Nichols {The Graduate} ![]()

Screenplay: The Graduate

Actor: Sidney Poitier {In the Heat of the Night}

Actress: Anne Bancroft {The Graduate}

Supporting Actor: Alan Arkin {Wait Until Dark}

Supporting Actress: Katherine Ross {The Graduate}

Cinematography: The Young Girls of Rochefort

Choreographers: Dale Moreda/Bob Fosse {How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying}

Art Design: How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying

Score, Non-Musical Film: Casino Royale (Burt Bacharach)

Musical Routine: Dance on the square {The Young Girls of Rochefort}

Song: Casino Royale {Casino Royale}

Animated Short: The Bear That Wasn’t (Chuck Jones, MGM)

Animated Feature: The Jungle Book

F&SF Feature: Quatermass and the Pit

The song Mrs. Robinson, from The Graduate, was incomplete, later completed for an album release, so it isn’t considered Oscar eligible, and I’ll keep to that view as it makes the song category easier. Art Design was a sparkling category; second place The Young Girls of Rochefort would have won in most years.

1968

-

The Lion in Winter

- 2001: A Space Odyssey

- Planet of the Apes

- The Producers

- The Shoes of the Fisherman

Most discussions of 1968 cinema, particularly cinematic awards, revolve around Oliver! verses 2001: A Space Odyssey. That’s a shame because the discussion should be, firstly, focused on the magnificence of The Lion in Winter. It is giants being portrayed by cinematic giants. It doesn’t have just the best performance of the year (from Peter O’Toole), but also the second-best (from Katharine Hepburn), and the third (from Timothy Dalton), and the fourth (from Anthony Hopkins), and the fifth (from John Castle). This is everything film acting should be. They don’t give us real people, but something more—something absolutely authentic, but not mundane. They are humans amplified, in an amplified (though soggy) world, using amplified dialog. The Lion in Winter is a film of powerful emotions and deep concepts; it’s beautifully executed and is the best film of the year and the third-best of the decade (My review).

Most discussions of 1968 cinema, particularly cinematic awards, revolve around Oliver! verses 2001: A Space Odyssey. That’s a shame because the discussion should be, firstly, focused on the magnificence of The Lion in Winter. It is giants being portrayed by cinematic giants. It doesn’t have just the best performance of the year (from Peter O’Toole), but also the second-best (from Katharine Hepburn), and the third (from Timothy Dalton), and the fourth (from Anthony Hopkins), and the fifth (from John Castle). This is everything film acting should be. They don’t give us real people, but something more—something absolutely authentic, but not mundane. They are humans amplified, in an amplified (though soggy) world, using amplified dialog. The Lion in Winter is a film of powerful emotions and deep concepts; it’s beautifully executed and is the best film of the year and the third-best of the decade (My review).

Its most talked-about competitor (though not in 1968 when it did not receive a Best Picture Oscar nomination), 2001: A Space Odyssey, is a complicated and layered film, with multiple conflicting themes and no single answer as to what it’s about. It’s fascinating, and while I question if Kubrick should have done all that he did, I do accept that he was successful in making what he wanted (My critique).

It was a good year for science fiction; the first to have two SF nominees. Planet of the Apes may not be as convoluted as 2001, but it isn’t a simple picture and it may even have stronger points to make. It has become so much a part of our culture that people forget how good it is (My review).

My next nomination requires me to ask a question: what defines a masterpiece? I downgraded Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolff? In 1966 for a few mistakes. With The Producers, it’s hard to find a scene that isn’t filled with mistakes. The edits are often amateurish and the framing is peculiar: sometimes people stand out of frame; sometimes they are just in the wrong spot. The lighting is mediocre, with grain appearing and disappearing (did they change film stock?). The extras seem not to be directed at all and the stars occasionally think they are on a theater stage. None of that’s surprising as Mel Brooks was new to directing and his leads were far more experienced with live theater. Yet, The Producers is a Masterpiece. An excellent script goes a long way in making it one, but The Producers reaches its heights not in the whole but for moments, moments that are memorable, hysterical, and relevant, moments such as the fountain, the meeting with the director, the writer’s response in the audience, LSD on stage, and the song Love Power. And then there’s Springtime For Hitler, one of the most audacious scenes ever put to film. Other shock moments from the 1960s have lost their power, but not this one. It still leaves me with my mouth hanging open, and even more so when I’m laughing. Sometimes a masterpiece comes without perfection.

There’s a drop after the top 4 to a pool of very good, but flawed films, that include Where Eagles Dare, Ice Station Zebra, The Odd Couple, Romeo and Juliet, and Oliver! I give a slight edge to The Shoes of the Fisherman, a roadshow picture filled with religious pageantry and political intrigue (My review).

As for the Oscars: Poor Oliver! Few films’ reputations have been harmed so much by winning. Every critic—and most everyone else who pays attention to film awards—thinks its win was a mistake. Most often it’s 2001: A Space Odyssey that it’s claimed was cheated, although both The Producers and The Lion in Winter have their supporters. Whatever the choice, the consensus is Oliver! didn’t deserve its win. But that doesn’t make it a bad film. It’s a very good film (My review). It makes my top 10 for the year and would be a FOSCAR nominee in four years of the decade. Just not this year.

The four other Oscar nominees were The Lion in Winter, Romeo and Juliet, Funny Girl, and Rachel, Rachel, in order of decreasing quality. The Academy has done worse. The Lion in Winter is far and away the finest of them, as I’ve already made clear, but Romeo and Juliet is a good film and a nice version of the play, finally giving us teen actors as the most famous teen characters of all time. It’s too slow and too respectful of the material, but it sits next to Oliver! in my top 10. (My comparison of multiple versions). The other two wouldn’t do quite so well, but then, they didn’t win and no one thought they would.

Funny Girl claims to be based on the life of Fanny Brice, but it’s even more a pack of lies than most biopics. If you’re inventing this much, why not just change the name of the lead and avoid slandering anyone? It shouldn’t be a narrative feature film, but a one-woman stage show. One, and only one, person sings. That’s usually a problem for a musical, and it is in this case. The book is bland, the romance is DOA, and the jokes aren’t funny. And Barbara Streisand, at a time when she had a great figure, playing the “Oh, I’m so ugly” bit is embarrassing. It was a third-rate Broadway show that had a few good songs (People, Don’t Rain on My Parade), and a lot of forgettable ones. Streisand can sing, and sings several of those songs very well, so buy the album, or a couple of singles; there’s no reason to sit through two and a half hours for that.

Rachel, Rachel was Paul Newman’s first shot at directing, and he was popular both personally and as an actor, and he wanted the nomination. So he pushed, and people smiled and gave it to him, with the understanding that was as far as it would go. Rachel, Rachel is an overly simple story of a lonely and emotionally stunted school teacher making decisions about her future. It’s unremarkably made, and not surprising for a film detailing a woman’s drab life, it’s a drab viewing experience. It moves too slowly and is too predictable to be of much interest.

Category FOSCARs:

Director: Stanley Kubrick {2001: A Space Odyssey}

Screenplay-Original: The Producers ![]()

Screenplay-Adapted: The Lion in Winter ![]()

Actor: Peter O’Toole {The Lion in Winter}

Actress: Katharine Hepburn {The Lion in Winter} ![]()

Supporting Actor: Timothy Dalton {The Lion in Winter}

Supporting Actress: Jane Merrow {The Lion in Winter}

Cinematography: 2001: A Space Odyssey (Geoffrey Unsworth)

Art Design: 2001: A Space Odyssey

Effects: 2001: A Space Odyssey ![]()

Makeup: John Chambers {Planet of the Apes}

Score, Non-Musical Film: Planet of the Apes (Jerry Goldsmith)

Song: Springtime For Hitler {The Producers}

Animated Short: Norman Normal (Alex Lovy/WB)

Animated Feature: Yellow Submarine

F&SF Feature: Planet of the Apes

What is the job of a director? Well, he’s got a lot of them, but what takes precedence when speaking of a great directing job? If it’s working with actors, then the clear winner is Anthony Harvey for The Lion in Winter. Sure, he had a fantastic team, all capable of amazing performances, but several were untested in ’68, and those that had been had faltered. He brought out the very best in them, some of the greatest performances of all time. And he did well with all the other pieces of the job. His competition, Stanley Kubrick, was never an actor’s director. He didn’t bring out anything more than they brought themselves. And I can’t recall anyone praising 2001 primarily for the performances. No one suggests that Keir Dullea’s performance was anywhere near Peter O’Toole’s. But for all the rest—connecting the thousands of different parts that make up a film—Kubrick was a master, falling under only David Lean. And 2001 may be the second most meticulously constructed film of all time, after Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia. It’s a hard call as it’s a question of what it means for a director to be great, and then greater. I made my choice for Kubrick, and I suspect I’ll get no arguments, but I wouldn’t debate anyone who took Harvey. The Oscar went to Carol Reed (Oliver!), so that’s no help, though they did nominate both Harvey and Kubrick.

Screenplay was a tie this year, so I broke it by using the Oscar’s categories, thus letting both win (and I am in agreement with the Oscars on the winners).

The acting categories are dominated by The Lion in Winter, and I need 2 more supporting awards as the 3rd Best Supporting Actor in The Lion in Winter would win in most other years. The Academy failed in a big way, giving the best actor award to Cliff Robertson for Charly; my how they love actors playing mentally disabled. O’Toole would never win, though they did give him an honorary award in 2003 because they recognized they’d really messed up. The only acting award they got right was for Katharine Hepburn—well, sort of. It was a tie between her and Streisand, which is ridiculous, but doubly so as they’d given Streisand a voting membership early, allowing her to vote for herself to create the tie. I can’t blame Streisand.

1969

-

Support Your Local Sheriff!

- Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid

- Oh! What a Lovely War

- They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?

- The Wild Bunch

I’d have never figured that 1969 would be the year of the Western. The genre was tottering and creaking, but then none of the three films on my list are traditional Westerns. Those were gone. In their place are deconstructions and comedies, and in two cases, both. The outlaws were the good guys and the “heroes” were happy to run away.

I’d have never figured that 1969 would be the year of the Western. The genre was tottering and creaking, but then none of the three films on my list are traditional Westerns. Those were gone. In their place are deconstructions and comedies, and in two cases, both. The outlaws were the good guys and the “heroes” were happy to run away.

Support Your Local Sherriff! is the funniest Western ever made. Its closest competition—and it isn’t that close—is Blazing Saddles, which borrows a good deal from Sherriff! (the townspeople could easily shift from one to the other). Support Your Local Sherriff! isn’t like the Western comedies of the ’40s and ’50s that celebrate the genre; it fits with this time and joined the 2nd and 3rd place films in signaling that the old Westerns were dead. It spoofs specific films (High Noon, My Darling Clementine, Winchester ’73) and the genre in general. This is great comic actors reciting great comic lines, fronted by James Garner doing a variation on the James Garner role. He plays a skilled gunman who is just passing through on his way to Australia (the real frontier) who takes the job of sheriff in a gold rush town and arrests the dimmest of the very dim Danby clan (Bruce Dern, who steals every scene he’s in) and must hold him in a jail without bars while his family schemes to get him out. Unfortunately, the original negative has been lost; current prints aren’t bad, but less than they should be.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid is the 2nd Western, and 2nd comedy one for the year—and comedies were needed as 1969 is filled with depressing pictures. Paul Newman solidified his status as the sexiest man alive, and Robert Redford rose up to join him. The film’s anti-establishment politics helped it climb the box office ladder, but it was the charm of its two stars, and their non-stop witty dialog, that kept it there. It’s hardly a Western at all—it’s a buddy comedy. It barely has a story. These two guys run around and chat. That’s it. It’s the quotable lines, and how they are delivered, that puts this on my nom list. It’s no deeper than that.

The Wild Bunch upset John Wayne (always a good sign) for taking the romance out of Westerns. It didn’t, as that had already been done, but The Wild Bunch was a bullhorn announcing that fact to anyone who had missed it. There are no heroes. There are no good men. There’s no great cause that anyone is fighting for. There are only tired, broken men who follow an immoral, pointless, cruel code and younger ones who have none at all. Director Sam Peckinpah, whose tendency for over-the-top violence has become a running joke, wanted to display the truth of ruthless men in the West while also tying in the meaningless brutality and corruption of the Vietnam War. He makes his points.

After the Westerns, the year slips. There are plenty of very good films, but no other great ones.

Oh! What a Lovely War is a surreal, star-studded, British, anti-war film. You could call it a dark comedy, but very dark. WWI is represented as a boardwalk carnival—sometimes—with songs and slides and lots and lots of death. The generals and politicians have no concern for the average soldier and there is never a chance of doing anything useful. The art design is first-rate, as is the acting. It goes on a bit long considering the point is clear in the introduction.

I choose They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? as one of the five best of the year, but it’s not one of my favorites. It’s hard to imagine that this is anyone’s favorite. It’s two hours of despair and misery. It follows wretched and desperate people battling for prize money in a Depression-era marathon dance contest. They find injury, insanity, and death. Things don’t become hopeless—everything was always hopeless—it just becomes even more blatant how hopeless life is. As a statement on the human condition, it may be more truth than you’ll want to see, but it sure does a good job of exhibiting that truth.

The Oscars had gone reactionary in 1968 with Oliver!, so they overcompensated this year, choosing as their winner Midnight Cowboy, an X-Rated (now light R) story of a male hustler, filled with rape and gay text and subtext. It’s a nearly plotless character study of two unlikely friends that is more successful than is comfortable revealing the unrelenting sadness of poverty in the US, and the hopelessness of dreams. But as the story starts nowhere and goes nowhere, I’d rather watch a documentary on the subject. Being “hip,” and shocking (at the time) won it a statue. It does contain a very good performance by John Voight (probably his best) and a great one from Dustin Hoffman.