Crooked Privy Councillor ten Brinken (Albert Bassermann) has had some success with his experiments with artificially inseminating rats, and wants to take it to the next level: inseminating a prostitute with the sperm from a dead murderer. Seems like that shouldn’t be the next level, but hey, I’m not a mad scientist, so what do I know? He enlists the aid of his nephew, Frank Braun (Harald Paulsen), who leaves after they kidnap a local loose woman. Frank is as close to a good guy as the film gets. I thought I’d mention that as usually kidnapping takes you out of the running to be the good guy. Anyway, seventeen years later, the result of the experiment, Alraune (Brigitte Helm), returns from boarding school, with no knowledge of her conception and thinking she’s ten Brinken’s niece. She’s a bit of a wild child, and has an enchanting effect on every man she meets, which leads to deaths and an upsetting of the social order. While everything is falling apart, Frank returns, because, as I mentioned, he’s the good guy, and Alraune takes an immediate interest in him.

Novelist Hanns Heinz Ewers REALLY didn’t like artificial insemination…A lot…In the running around waving his arms in the air and yelling “fire” way. He also wasn’t fond of women not keeping to their place. But he did think eugenics was pretty cool. I think it’s fair to call him a reactionary. Of course him becoming a Nazi is the cherry on top.

Director Richard Oswald wasn’t any of those things. He was Jewish and progressive, and while never a great artist, and more interested with cranking out films than quality (he averaged 25 a year during the silent era), he wanted to make statements about how it wasn’t birth, but society that was to blame for the nation’s woes. The problem is you can’t take a work of fanatical right-wing, religious gobbledegook and swap the themes, not without a lot more skill than Oswald had.

Alraune was a very hot property in Germany. This is the fourth (or fifth—the records are unclear and several films have been lost) cinematic version, and there would be another in ’52, long after artificial insemination became socially acceptable which makes its premise feel a bit silly. Alraune’s the first female movie monster and the only one to support a series in the classic and pre-classic days. That the story is so regressive doesn’t say anything good about how women were (are) viewed.

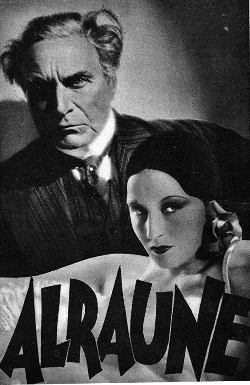

The 1928 version was a hit, diving into the murky morality, but mainly shining due to the performance of Brigitte Helm a year after her star-making turn in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. Her Alraune was the ultimate femme fatale, oozing sex and evil, yet still sympathetic. You like her, and you want her to win. People bought tickets to see her vamp about silently, so producers, being what they are, thought hey, why not do it again just two years later, but now with talking. They even re-hired Helm, though everyone else was new.

Putting eugenics and artificial insemination and the role of women in society on the backburner (but don’t forget them as they fill this story), Alraune is a variant on Frankenstein. We’ve got a mad scientist, obsessed with creating life for questionable reasons. He does so, but then his creation doesn’t turn out the way intended, and when it’s treated poorly, it strikes back. Alraune is soulless due to the nature of her birth, and as she’s a woman, her strength is in her sexuality. She doesn’t, for the most part, feel, and has no notion of right and wrong. OK, even with all that stuff on the backburner, this sounds pretty terrible. And philosophically, it is. The film versions that more-or-less work do so either from the power of the characterization (1928’s) or on style and design (1952’s – My review). This version has neither of those. Oswald, in his failed attempt to fix the message, sucks the energy out of the story.

Oswald moved the time period to the then-modern era. That means gone is the Gothic, fairytale feel and the expressionism, and in comes the mundane world. Gone as well is any hint of magic, and when you are dealing with soulless, sex-crazed unnatural women, magic really helps. But then it’s no longer clear that she is soulless, and she isn’t presented as sex-crazed but instead surrounded by comically inept men (she asks the guy to pick her a flower and he flops into the water and drowns). With those shifts, Alraune ceases to be a horror movie, becoming a melodrama, and a rather dull one. Since this time Alraune isn’t a succubus, Brigitte Helm’s smokin’ routine wouldn’t work, so she tones it down to the point I wouldn’t have recognized her without the credits. We get no sultry glances, no jerking mannerisms. Before she’d been mesmerizing and unreal. Here she’s conventionally attractive and ordinary. Helm isn’t to blame as no one is memorable except for Bassermann, who seems to relish his grumpy, thieving, incestuous role as the mad scientist. But one living character isn’t enough.

Alraune is morally repugnant. Far worse, it’s boring. Choose a different version.