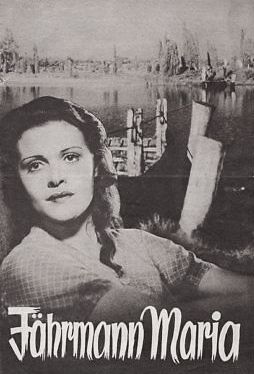

The local ferryman meets the personification of death (Peter Voß) one night, and dies on his ferry. The town advertizes for a new ferryman, but there are no local takers as the townspeople fear an evil force roams the other side of the river. Maria (Sybille Schmitz) wanders into town, lacking papers, so is a criminal. But she’s given the job of ferryman, along with a hut adjacent to a swamp. One night she’s summoned to the other side of the river by a wounded man (Aribert Mog), who says he’s being pursued. Maria ferries him across, nurses him, and falls in love with him. Soon after, she is summoned again, this time by Death, who insists he must find the wounded man before sunrise.

This is an interesting one. In 1936 the Nazis were in power and filmmaker Frank Wisbar was already on the wrong side of Joseph Goebbels; He’d worked on a lesbian-themed film, made movies with dark, psychological themes, and had a Jewish wife. He tried to thread the needle, making Rivalen der Luft – Ein Segelfliegerfilm (1934), a film that pandered to nationalists. Not surprisingly, it didn’t work and after making a few more pictures, including this one, he fled Germany for the United States. He picked up work on Poverty Row production, eventually remaking Fährmann Maria, with a tiny budget, as 1946’s Strangler Of The Swamp.

Things didn’t work out for Sybille Schmitz either. She’d become a star, but her non-Aryan look relegated her to lesser roles. That she had any roles during the Nazi regime meant no one wanted to touch her after the war and she ended up an addict and mentally unstable, committing suicide at 44 with the aid of a shady doctor who was stealing from her.

Fährmann Maria (Maria, Ferryman) is the last gasp of German expressionism. Wisbar tried to balance the twisting style with exteriors shots of landscapes and a nod toward folktales, but it wasn’t nearly enough for the Nazis. While it isn’t hard to read pro-Nazi sentiment in the story (the wounded man expounds on the wonders of his homeland, and how every man must fight because there are so many enemies), it is even easier to read an anti-Nazi subtext. Death has a very Aryan look and totalitarian manner, while Maria is a refugee that can be seen as a Gypsy or Jew. Maria’s idea that her love for the wounded man will give her a new home puts love over race, a fact that was noted by party adherents. Goebbels despised it, but chose not to ban it as he was winning the propaganda war, and didn’t want a fight over what turned out to be a popular and artistically lauded film. And he was clever as he didn’t need to. Most of the other classic directors were already out of the country and his chosen ones (like Riefenstahl and Harlan) would usher in an era of Nazi propaganda pictures. There wouldn’t be another film like Fährmann Maria.

I’m writing more about what surrounded the film than the film itself, but context here is everything. What I see while watching this film and how it makes me feel is effected by what swirls around it. The imagery is often compelling, particularly when Maria is tugging on the rope that moves her boat slowly through the water, but it means so much more realizing she is non-Aryan and Goebbels was watching, and that Schmitz would have her own confrontation with death relatively soon. Like Triumph of the Will, it can’t be considered in a vacuum.

It has the feel of a top rate expressionistic film from 1930: artistically advanced but technologically regressed. This is essentially a silent film, with the story told with shadows, lingering shots, and over-emotive expressions. Is that a problem? A line can be drawn, starting at The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), through Nosferatu (1922), and ending—snipped off—at Fährmann Maria, and when considered that way, with its kin, then no, it isn’t a problem. This is a movie of a different kind than we are used to in the sound era or in America, with a different cinematic vocabulary, and it needs to be judged for what it is. A movie about death takes on extra meaning when it is the last of its line in so many ways.

That connection to Nosferatu runs deep, not just style, or even theme, but story as well. There was some borrowing going on, but then Begman plundered Fährmann Maria for The Seventh Seal, so fair is fair.

At 85 minutes, Fährmann Maria is long. The story could (and partially did) fit into a half hour Twilight Zone episode. Wisbar and company add in a drunken violinist to fill in some time, but otherwise this is a very simple and direct fairytale. I’d have preferred more complexity, or a shorter runtime. And while it conveys the mood intended, Wisbar is no Lang or Wiene or Murnau. In their hands, this might have been a masterpiece; in Wisbar’s, it is interesting and a must-view for anyone interested in the history of horror on film.