Lord Hanabasa assures his two children that recent earthquakes are not to be feared as their good god will protect them. The common villagers have a different view, gathering to perform a ceremony to keep an evil spirit locked away in a giant statue. Samanosuke, the traitorous Chamberlain, takes advantage of the confusion to murder the lord and seize control, but fails to kill Hanabasa’s children. Protected by a swordsman and a priestess for ten years, they come of age hiding on their god’s mountain. The rightful heir sets his mind on freeing his people from Samantha’s cruel rule, while that evil man decides to crush the villagers’ spirit by destroying the giant idol, both actions potentially causing the massive “Majin” to awaken.

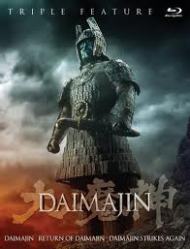

Discovering the Daimajin movies twenty-five years after their release was a delightful surprise. Good daikaiju is rarer then a funny Ben Stiller movie (percentage-wise) and a period one with samurai… Well, to the best of my knowledge, these are it. All three were made in 1966, and released a year apart. The studio had hit pay dirt with Gammera, the gigantic turtle, and were looking for another giant monster franchise; something different. They found it.

At first I was loathe to categorize Daimajin as daikaiju. It feels like a straight samurai adventure, with a bit of Hong Kong fantasy mixed in toward the end. But city stomping is an automatic entry pass into the daikaiju club, and Majin gets in some good stomping, even if the buildings are a bit more primitive than normal.

Perhaps it is just that I am so used to the human story being unimportant filler between monster misdeeds (see about 20 of the Godzilla pictures). Here the story, not the smashing, is the point, not that the smashing isn’t worth the price of admission on its own. The story is a simple heroes tale, like 90% of Japanese sword epics, with that simplicity strengthening the drama. The characters are well defined, and pure, good or evil as the case may be.

There is on exception: The god. He’s a world of contradictions. It is not clear if Majin is “the god” but no one else shows up to lay claim to the title. If he is the good god that is mentioned, he’s not all that sympathetic to his people’s pain, as only a personal insult and a woman’s tears gets him moving, and collateral damage doesn’t phase him. If he is the demon the villagers feared, he’s amazingly just (Old Testament just) and a better neighbor than many of the humans. It leads to a fascinating world.